It’s almost impossible to read anything in the business press these days without coming across the term “inflation” and hearing about which companies have announced price increases this week. (In case you missed them, here are posts that we did on inflation: from April and then a follow-up to a webinar we conducted in late May.)

It’s almost impossible to read anything in the business press these days without coming across the term “inflation” and hearing about which companies have announced price increases this week. (In case you missed them, here are posts that we did on inflation: from April and then a follow-up to a webinar we conducted in late May.)

Before a company decides to increase prices, in theory a lot of work is done to determine the likely impact of that action on volume, revenue and profit for the manufacturer and its retail customers. However, in the face of rapidly rising costs, it is not unusual for finance and/or management to insist that prices go up to maintain profit margins. The key to figuring out a likely realistic impact on volume (and therefore revenue and margin) is price elasticity. The concept of elasticity in general is used to determine how much a change in a business driver affects the demand of product. Price elasticity is probably the most commonly used elasticity but there are also analogous measures for distribution, trade, advertising and other business drivers. (You can see how elasticities are applied to different business drivers when doing a volume decomposition in a 6-part series from a few years ago. See the first post here which has links to the other 5 in the series at the end.)

Things to know about price elasticity for the vast majority of CPG products:

- Price elasticity is always negative. This makes sense because when price goes up, demand goes down. But wait, you may be thinking! That hasn’t happened over the last couple of years – we’ve been able to raise price and our volume has not really declined (or has increased). That’s because…

- Consumers’ sensitivity to price changes (what elasticity is measuring) is affected by many different things. Sales of toilet paper, hand sanitizer and many other things (foods cooked/eaten at home more, anyone?) continued to increase as prices also went up throughout 2020. Obviously there were “special circumstances” surrounding demand for all products but that does not mean that the usual relationship between price and demand is no longer valid.

- Based on my 30+ years of experience across LOTS of product categories, price elasticity is usually something between about -2.8 and -0.7. For the vast majority of businesses I’ve seen, it’s between about -2.4 and -1.2. (IRI and NielsenIQ have both shared research that shows price elasticities have changed very little, even during the last couple of years.) The larger the elasticity is in absolute value the more sensitive consumers are to a price change.

- Before anybody asks in the comments…price elasticity cannot be accurately estimated from the market level, aggregate data available in a typical NielsenIQ/IRI/SPINS database. There is usually a lot more than price that is changing at the same time plus the prices you see are averages across a bunch of stores, not necessarily the prices that shoppers are actually responding to. Data needs to be analyzed at the item-weekly-store level. Price elasticity work is typically done thru the data supplier’s or an internal advanced analytics custom projects group (or a consultant with data access and modeling expertise). Sorry, but we will not get into how to determine price elasticity. The remainder of this post assumes that you already have that estimate.

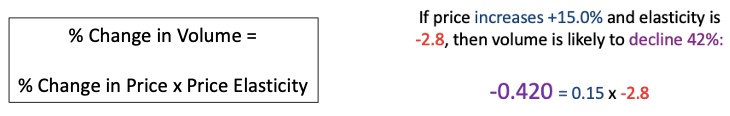

We recently received a question from a reader asking about which of 2 different formulas they should use to estimate the volume of a price increase, given that they know the product’s price elasticity. The formula that people usually know and use should be considered the “quick & dirty” version but there is also the more correct real formula. I’ll explain how to use both and then show when the “quick & dirty” may not be sufficient. Let’s use the data submitted by our reader to illustrate.

Example:

- Elasticity -2.8 (consumers are very sensitive to price changes for this product!)

- Proposed price change +15% (not that unusual in 2022 but quite large in more normal times)

Quick & Dirty Formula

So this shows that a price increase of +15% on a product that is very elastic is likely to result in a volume decline of 42%. That seems like it might be too much of a decline. Let’s see what happens when we use the official formula.

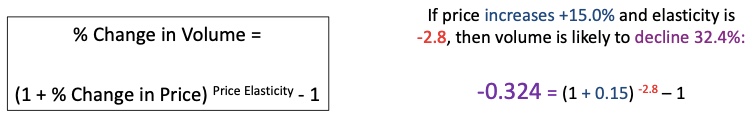

Official Formula

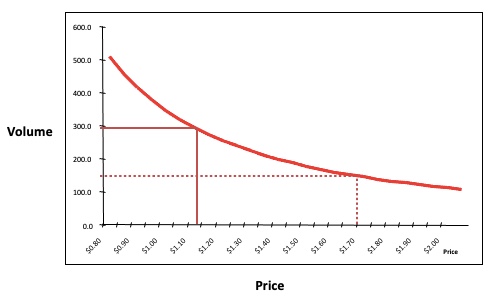

Now it says that volume is likely to decline 32.4%, almost a 10-point difference than when using the Quick & Dirty formula. That’s because the fancier formula, raising something to a power, results in a price-volume relationship that is not linear. When the price change is small (moving to the right a little on the x-axis below), the curve is pretty close to a straight line. But, when the price change is large, the curve is not as steep as a straight line. You can also see that the curve is not symmetrical – a 15% price increase does not affect volume as much as a 15% price decrease does. Volume is likely to increase faster when the price goes down than it declines when the price increases. A price cut attracts new users/brand switchers while there is usually a group of loyal users that will continue to buy even when the price goes up.

Sample Demand Curve

When is the Quick & Dirty Formula OK to Use?

That formula gives you a result closer to the official one when two things are true:

- Elasticity is closer to -1.0

and - The magnitude of price change is within 10-15% of the current price.

So for this example I would go with the second formula and -32.4% likely change in volume. Since it’s easy enough to put the real formula in Excel you might as well use that whenever doing these kinds of calculations.

Click here to open and save an XLS file that has both formulas and a comparison of the resulting volume change for a 10% and 20% change.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to future posts via email. We won’t share your email address with anyone.

Do you think I can apply the same formula for a customer that is taking a price DECREASE? Yes, that’s right, a decrease! Customer is dropping their pricing by 30% to get closer to it’s competition. Does anyone have a formula for this?

Yes, you can use the same formula. Definitely use the “official” formula, not the Quick & Dirty. A 30% price cut is very big but has the potential to erode brand equity – consumers may wonder if the formula has changed to be lower quality. Go ahead and download the XLS file in the post and then you can modify the price change in the tables to see what happens to volume. You can enter -30% but also, say, -10% and -20%. Depending on what the price elasticity is the volume increase could be huge!

Thank you, Robin. This article gives small, growing brands an idea of how to look at pricing correctly.

Hi Robin – Thanks for this article. I am not clear on how we are coming up with official formula. I have always used what is called here as “quick and dirty”. Always thought elasticity is estimate as % in volume/ a 1% change in price. Can you please clarify on how you got to official formula.

thanks

I learned the official formula in graduate school and we used that formula in most analyses at Kraft Foods since the late 1990s. I don’t know/remember who originally came up with the official formula” but I’m sure it was an economics professor wanting to depict the non-linear nature of human behavior that has been observed. The quick & dirty formula is obviously easier to use and understand but simplifies what happens in real life. Here’s an article I was able to find on price elasticity where they say “The demand curve is linear in its most basic form and its slope represents the probable purchase quantities at various prices.” (emphasis added by me)

Hope that helps!

The formula my teams and I used for “quick and dirty” when I was at Nielsen:

(new price / old price) ^ elasticity – 1

When you’re working with promo elasticity you’ll also have things like promo multipliers – but again simple math.

Quick and dirty is good to start the ball rolling – but it’s really important to understand other factors too, including category health, your place in the category, your gap to your competition, etc. A quality elasticity model should be able to express cross-elasticity, price thresholds and have software that’s both easy to use and can let you do both quick calculations and – as you’ll inevitably end up doing – trade plans

Thanks for the comments – all valid points. There are some variations for how to apply the price elasticity. Most people looking for quick and dirty are applying a formula to average price, when in theory the price elasticity should be applied to base price and “supplemented” with promotion multipliers and lift by tactic. I totally agree that a good elasticity model should include cross-elasticities and thresholds but many companies (especially smaller ones) don’t have the budget to spend on that and/or want an answer very quickly. Having software that incorporates the results of a good elasticity model is a huge help!

Hi Robin,

Thanks for this post. Quick Question – Why should we apply pricing elasticity on base price and not on actual price ? (Store wise Price at item level /day level).

The base price is not the actual price which is seen by a consumer during promo weeks and hence calculating unit change basis the base price change doesnt seem intuitively right.

I agree we cant take average price either as it is not the right price.

Why do analytics providers calculate base price elasticity separately and promo elasticity separately ? And how do we calculate promo price elasticity ?

Appreciate your help.

Thanks

Your questions get to the reasons for having Nielsen/IRI/another analytics supplier conduct a rigorous price-promotion study! That study uses item-store or chain-weekly data and does account for both base and promoted prices when each are in fact seen by consumers. Promo elasticity is usually expressed as a positive number – how much do sales go up for each % point of discount. Note that it is based on % discount from base price and not the promo price itself. Promo elasticity is always provided along with lifts or multipliers for each of the trade tactics, too. Calculating promo elasticity is too complex for a quick explanation here but your Nielsen/IRI client servce rep should be able to get you an answer to that.

Thanks for your post. It helps clarify a lot of concepts.

I am trying to make a Price Elasticity model in my organization, trying to calculate Price Elasticity. I work in snacks company having multiple categories. I have Invoice wise SKU wise distributor level data with a visibility of primary sales only (means that the SKUs leaves the factory to reach the distributor, only that data is available). Can you help me on how to go about it?

Unless you are able to get data that measures how much consumers/shoppers are buying and at what price you really cannot get to a true price elasticity. Using data on your sales to distributors could get you a rough estimate of the distributors’ price sensitivity but not the shoppers’. Ideally you’ll need to aggregate SKUs into groups that are sold at the same price and calculate at the distributor level, as some will be more price sensitive than others. The quickest way is to look at % change in physical volume divided by percent change in price over several periods of time. This assumes that the price does show some variation. If the price has not really changed that much then this will not work. You also want to be careful about what else was happening at the same time that price was changing so that you don’t over- or under-estimate the price elasticity. As you probably know, this is not a simple thing to calculate!