This is the next in our series of posts about retail pricing. In this post I’ll talk about price gaps – how to calculate them and why they’re important. (You may want to review these previous posts before continuing: retail pricing in general, base price, discount, and trade merchandising measurement.)

Take a moment and imagine a world where your brand has no competition. Wouldn’t that be great? If somebody wants to buy a product in your category, they have to buy your brand and you can probably charge a lot more than you do now, since consumers don’t have a choice! Now…come back to the real world. If you’re lucky, you have some very loyal consumers who automatically buy your brand and don’t even consider anything else. If your brand is like most, however, there is a large group of consumers who have some set of brands that they consider whenever they are in the market for your category. That’s where price gaps come in. Price gap is the difference in price between your product and the competition.

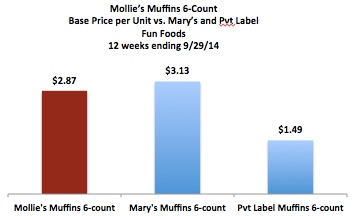

Take a look at the following base price data in the retailer Fun Foods (base price is the IRI/Nielsen estimate for regular price):

(Throughout the rest of this post, assume that your brand is Mollie’s Muffins.)

Calculating Price Gaps

There are 2 ways to think about discount and shoppers do consider both of these, either explicitly or subconsciously. You should look at both of these measures for your major sizes/PPGs vs. your key competitors, both branded and private label.

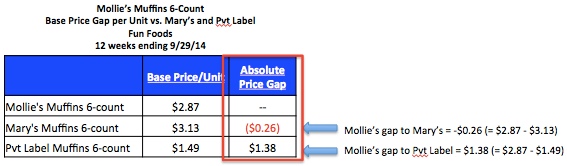

Absolute gap is the amount that your price is above or below the competition, expressed in dollars or cents.

![]()

So using the data from the example above, here are the base price gaps of Mollie’s 6-count vs. its key competitors:

I recommend subtracting the competitor’s price from your price, not the other way around. This frames the gap in terms of how you compare to everybody else, which is what you are most concerned with since you are managing your own price. In our example we see that our base price is 26¢ lower than Mary’s and $1.74 higher than Private Label.

Price gap is not usually a database measure provided by Nielsen/IRI, so you have to calculate it. There are thousands of products in any given category so there would be literally millions of possible combinations used to create price gaps! You need to decide which key products you want to track price gap for and create those calculations yourself. Be careful not to bite off more than you can chew! Note that you can calculate gaps for any of the pricing measures: base, promoted, quality etc. In this example we are looking at base price.

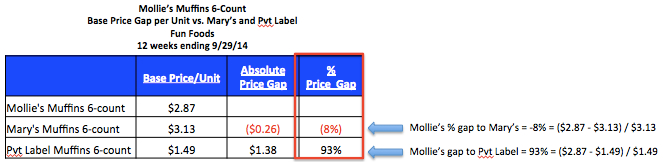

% gap expresses the amount as the percentage that your price is above or below the competition:

![]()

I recommend having the competitor’s price in the denominator, not your price. Again, this frames the % gap in terms of how you compare to everybody else, which is what you are most concerned with. In our example we see that our base price is 8% lower than Mary’s and 93% higher than Private Label. Be careful if you are looking at % gap data created by someone else – make sure you understand what was in the numerator and what was in the denominator, since not everyone consistently follows this standard.

Comparing Price Gaps

Here are some common ways that comparing price gaps can help inform your price-trade strategy:

- Current price gaps vs. key competitors – Most brands like to maintain a particular price gap to specific competitors – “we want to be at least 10% lower than Brand X” or “we want to be no more than 50% higher than Private Label.” IRI/Nielsen data allows you to track how you are doing against these objectives. If you don’t have a price gap strategy, assessing price gaps is a great way to get started thinking about this issue.

- Price gaps vs. year ago – Even if your own price has not changed, it is possible that your price gap to competition has changed. Remember that it takes two to tango (and to have a price gap). If you see that price gaps are widening (and not in your favor), check to see if the gap is increasing because of changes in your price, the competitor’s price or both.

- Price gaps in different retailers – are shoppers seeing different price gaps in different stores? Most brands like to maintain a consistent brand image in the marketplace and almost all consumers shop in more than one chain.

- Price gaps between organic products and their conventional counterparts – this is really a special case of comparing to key competitors. Many retailers manage those segments completely separately, thinking that there is an “organic consumer” and a “conventional consumer.” But in fact that is not always the case – those two segments often interact. You can tell that this is happening when growth rates shift between organic and conventional items when a retailer has especially dramatic promotions on one or the other.

How do you think about price gaps? Is it different than what I’ve talked about? Leave a Comment for this post.

If you enjoyed this article, subscribe to future posts via email. We won’t share your email address with anyone.

Leave a Reply